On Sunday it will be six months since Kieran died by suicide.

One of the strangest things about being bereaved is what I’ve come to call the doubling of grief, the destabilisation of two contradictory things being true at once. My life is simultaneously utterly different from how it was before, my entire present turned upside down and the future shaken out and lost, and also very much as it always was. Our daughter still goes to ballet on Tuesdays after school; I still make us pancakes on Sunday; the daily reality of my job is much the same. There is a comfort in that and there is a strangeness to it. I have heard people who experience depersonalisation talk about how they can touch their own face and yet feel like it is something alien and strange, nothing of themselves. Sometimes I can look at the ordinary comfort of my daily life and feel that it, too, is briefly alien flesh under my fingers.

For the most part, though, I lean into the comforting reassurance of what stays the same; what I have managed to keep the same. What I have the privilege to keep the same, because many people in my situation risk losing their homes, see their whole families fall apart, find themselves unable to work. It is a daunting thing, sometimes, to know just how close the edge of the cliff called there but by the grace of God go I actually lies, and to understand more completely that God’s grace is in many ways as alien and relentless as the process of grief.

Last weekend I hosted a party to honour Kieran; a proper celebration of his life, since his funeral had to be a short, pinched sort of thing under covid restrictions. We did the best with what we could, and it was as nice as it could be, I think; but for me, from a Catholic family used to wakes, half an hour in a crematorium with no reception was too mean for a person as generous-spirited as my husband. It was a lovely party. I smiled a lot; I cried once, sharply and briefly; and I was glad to be in a room full of people who loved Kieran. I think it did everyone else good, too.

So. The funeral is done, the memorial is done, the bills are in my name, the inquest is over. Probate is still not quite settled, but will be soon. Finally, after six months, nearly all the administration and commemoration is wrapped up. Things will keep coming up, of course, but in many ways, this part of the portion of grief is over.

What now? I asked my therapist, and myself, when I spoke to her this week. Sometimes I am in the middle of something perfectly ordinary and feel a deep horror that this is it forever. This perfectly nice, good life that I have now, where I walk around and often laugh, feel happy and satisfied – a life where I do all that with a hole punched in my chest, and that even as it gradually heals, the thing that has been lost is never coming back. I understand why many grieving widow/ers I come across so closely hold onto the paraphernalia of their loved ones, keep themselves wrapped up in their clothes and leave their desks untouched. I can see the comfort in that. Certainly there is plenty in the house to remind me of Kieran, but I am wary of giving all my emotional attention to the past. Years ago I read a poem by Robert Graves that has stuck with me:

To bring the dead to life Is no great magic. Few are wholly dead: Blow on a dead man’s embers And a live flame will start. Let his forgotten griefs be now, And now his withered hopes; Subdue your pen to his handwriting Until it prove as natural To sign his name as yours. Limp as he limped, Swear by the oaths he swore; If he wore black, affect the same; If he had gouty fingers, Be yours gouty too. Assemble tokens intimate of him — A ring, a hood, a desk: Around these elements then build A home familiar to The greedy revenant. So grant him life, but reckon That the grave which housed him May not be empty now: You in his spotted garments Shall yourself lie wrapped.

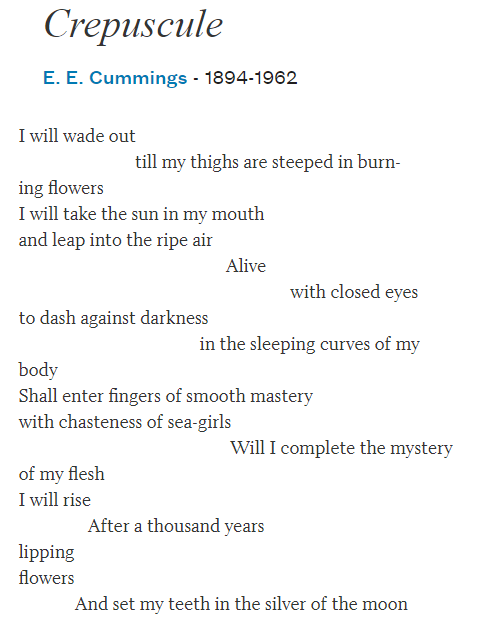

There’s a querulous sort of moralising to the tone of it I don’t especially like, but I do have an instinctive sort of dread of those spotted garments. I am not ready for any kind of grave, including one I dig inside my own chest. No; I may have a great hole blown through me, but if it causes me pain, it also lets light in. This morning I was reminded of another poem, this one a song – at least in my reading of it – of a leap of faith against the dark.

To take the sun in my mouth is an act of daily defiance; it is my still unshaken belief that it is a good thing to be in the world and of it, to put myself into the ripe air and perhaps, one day, set my teeth in the moon. These are impossible times; I will believe in impossible things. Cummings asks a question in the poem but does not cap it with a question mark; the question of completing the mystery that is ourselves is, after all, a line that deserves to be left open.

Dear Rachel, I read your article in Metro and have now read some of your blog posts. They moved me. I am almost 70 and my son, my only child, ended his life by suicide in June, aged 43. When people ask me that impossible, draining question, how are you? — a query I shudder from, even though I know they’re doing their best — I now reply that I’m bonkers. I’ve given up with ‘OK thanks’ and it does encapsulate how I am. I’ve become a split personality; I can laugh, write, smile, watch TV and read while howling silently. I respect my son’s decision but I feel abandoned. I admire your lack of self-pity in your writing. Thank you for the honesty in your words. Complex grief is such hard, exhausting work, a job we never applied for.

All best wishes to you and your daughter, Gretta.

I’m so sorry that you too have experienced this painful loss. What a terrible thing that your child, the precious body you grew and nurtured, is gone before you. It’s wrong and I’m very sad you have to carry this sorrow. Love is a hard weight to carry sometimes. But despite everything I haven’t regretted that I met Kieran and married him; I wouldn’t trade it away even if it meant getting rid of the pain I feel now. I’m sure you would say the same. That will have to be enough. Xx