This morning human remains were found in woodland in Kent. Remains: what a stark word. What remains of a person described as “beautiful, thoughtful and incredibly kind”; what remains, in all likelihood, of a person who was Sarah Everard, a woman close to my own age, even with the same sort of hair as me – dark blonde, a persistent wave – who walked through public parkland and was probably then kidnapped and murdered, and whatever else came between that and then. Remains: something dehumanised, fragmented.

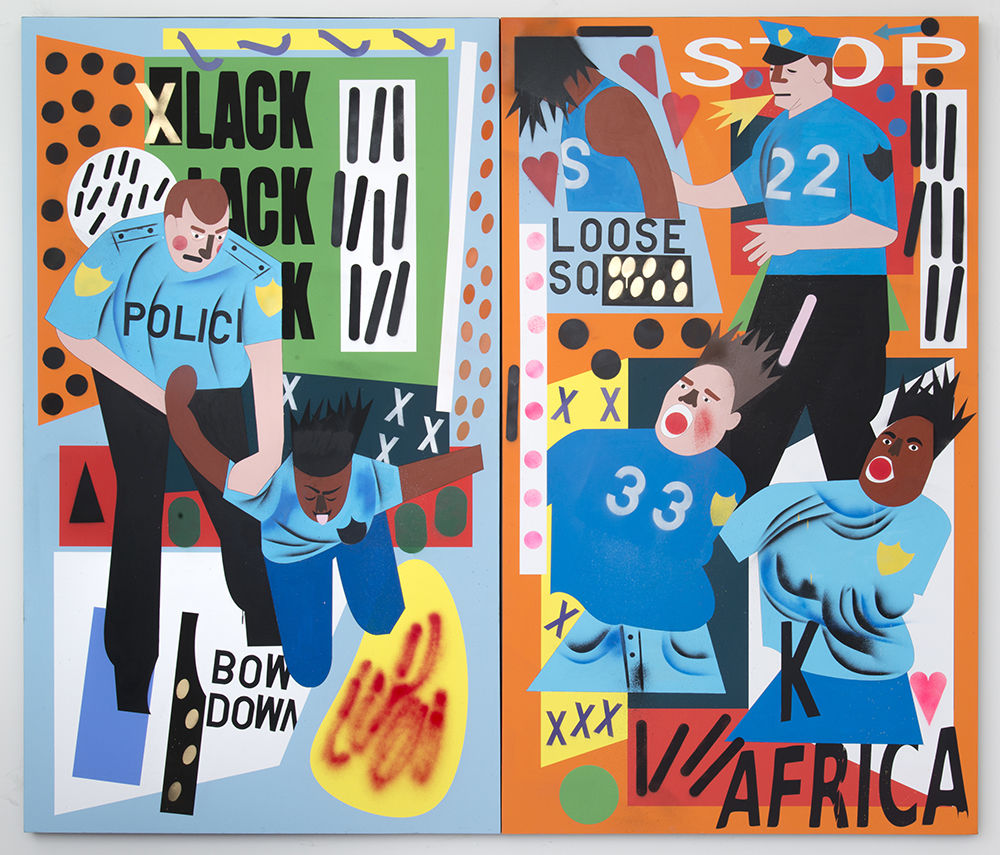

It’s easy for women to go through the world feeling that way. This morning I took an art collage workshop inspired by the work of Nina Chanel Abney, and I ended up making a pregnant woman, beheaded, holding her own snaky hair.

Yesterday on twitter, outraged by seeing comments that said Sarah Everard shouldn’t have walked home alone at night, a few women started sharing their experiences of being scared walking home or travelling on public transport, being harassed and scared. More and more women started sharing their own experiences after that, and there were lots of posts of the type asking women to like or retweet if they’d ever walked home with their key between their fingers as a potential defensive weapon, or had got off a bus early because another passenger was making them uncomfortable.

I was tempted to throw my own stories into the ring. I’ve got plenty, after all, and there’s something cathartic about it. But something held me back, too, and it wasn’t shame about my stories. I tweeted:

Sometimes I feel like sharing our stories is a game of chicken.

Oh, we’ve all been shouted at on the street, haven’t we?

We’ve all been followed?

We’ve all been groped?

Waiting for a story that we haven’t been part of yet, to feel the giddy lurch of relief and fear.

A wise friend of mine pointed out that the sharing of these stories keeps us hypervigilant, keeps us afraid, and that the fear is the point. I’ve often thought about this, how we’re taught to be afraid on the streets but to stay quiet about problems at home, how while most of us are subject on the street to regular low-level harassment by cis men (which is definitely not ok) the place we are most likely to be hurt is where we live. (That goes for men too – 1.3 million women and 750k men in the UK last year were victims of domestic abuse.) Sarah Everard was murdered this week, by a man who was probably a stranger to her. Every week in England and Wales two women are murdered by their partners, in violence horribly mundane enough to rarely get on anything other than local news.

This is not intended in any way to diminish the significance of Sarah Everard’s death, or the fear it inspired; nor is it intended to diminish the everyday anxiety so many of us – everyone who identifies as a woman or who has been assigned female at birth – feel about being out in the world doing ordinary things, feeling vulnerable because we are socialised to see ourselves as at risk from cis men and also because we are socialised to understand that if the worst happens, it will be our fault. Hell, I wrote about this in my book back in 2013 –

The fifteenth century poem Why I Can’t Be a Nun blames Dinah [biblical figure from the Book of Genesis] for her rape because ‘for sche bode not stylle, / But went owte to see thynges in veyne’. In effect, to use a more modern term, Dinah was ‘asking for it’. The implication that harm, both physical and spiritual, will come to women who leave their proper sphere is found in Caxton’s The Knight of the Tower, a 1483 translation of the fourteenth-century Livre pour l’enseignement de ses filles du Chevalier de La Tour Landry. In one of the knight’s stories, a woman goes out at night to see her lover, and ‘she felle in to a pyte whiche was twenty fadom depe’. She is miraculously saved after praying and repenting. She seems to be guilty of both the sexual misconduct of having a lover and social misconduct: that is, leaving her home at night. It is easy to blur the line between these so that the act of leaving the appropriate feminine space of the house for the physically dangerous outside world becomes associated with falling into a ‘pyte’ of sexual misbehaviour. If a woman goes ‘as it were a gase / Fro house to house to seke the mase [diversion]’, she will reap the consequences.

I don’t know what the solution is. Fear is a necessary part of patriarchy, and it is a very clever part. It’s not just a blunt weapon like a fist. It’s also a weapon that erodes your confidence, prevents you from doing things you love, from growing new connections, from feeling free. And importantly it is a weapon that can be used to galvanise those of us who are marginalised to turn on those who are marginalised even more. Marian Bleeke, writing about the alt-right protestors at Charlottesville in 2017, noted the way they weaponise white femininity:

In a post on her blog, Wife with a Purpose, entitled “Women’s Roles in the Movement,” Ayla Stewart gives her reasons for backing out of an agreement to speak at Charlottesville and then deciding not to attend the protest. She explains that, as the event grew in scale, she came to feel “out of place” speaking there, because she saw speaking as a role for leaders and not for a mother. This explanation implicitly genders leadership, identifying it as a masculine role by opposing it to her identity as a mother. She then adds that the expectation of violence at the event convinced her security team that it would not be safe for her to attend. This comment identifies femininity with vulnerability because there was a concern for her safety, but apparently not that of male protestors.

We are in a double bind here. The threat of being raped and murdered by a stranger is vanishingly small, but is so terrible that we dread it – a dread exacerbated by all the things that happen to us on a daily basis that make us think about the small steps between that and being found buried in woodlands. When we talk about the things that happen to us, we feel some catharsis, some lifting of a burden, and when others share their own experiences we feel solidarity in the sharing. But what that sharing often does is retraumatise us, make us feel more afraid. We have to find a way of sharing that is about shouldering a shared burden and finding a way to get rid of it, not sharing in a way that smothers us together. I hope that we can take our righteous anger and fear and turn it out against a system that demonises and infantilises us, not turn it inward against other victims of patriarchy. We all deserve much more than that.

Brilliant piece Rachel.

Thank you!

Thank you for writing such a thoughtful post about this horrific incident.

Jo Van Every Academic Career Guide & Academic Writing Studio

Website: https://jovanevery.co.uk Sign up for my newsletter: https://jovanevery.co.uk/newsletter Twitter: @JoVanEvery

>

Thanks very much!

Thank you. Keep speaking truth!

Thank you, Rachel. So wise, heartfelt, and important.

Thank you!