Over the past few days, 53,000 people have retweeted a thread about Agnes Sorel, mistress of Charles VII of France. How cool – a popular thread about a medieval woman! Except that the thread is misleading at best. Jennifer Wright wrote: “Here’s Agnes Sorel, who had her gowns tailored to expose her favorite boob in the 1440s.” The two images chosen to illustrate this were a very famous painting by Jean Fouquet, and a sixteenth-century painting inspired by Fouquet’s. Fouquet’s portrait is fascinating not because of the bare breast per se, but because it depicts the mistress of the King as the Virgin Mary – specifically, as the Virgo Lactans, or the Nursing Virgin, a popular iconographical trope of the Middle Ages that connected Christ intimately to His human nature by showing He, like any other child, was fed by His mother’s breast.

That Sorel, who gave Charles four children and had a reputation for scandalous dress and behaviour, should be portrayed as the Mother of God is a very bold choice. Of course it’s tempting to think this choice was made because Sorel had already established a fashion for bearing her breasts – a claim made on her Wikipedia entry and in pretty much every article Google throws up if you search for her name. I have only been able to find a couple of primary sources that give any indiciation that Sorel bared her breasts in public, quoted within Sheila Delany’s academic survey of social constructions of the body in the fifteenth-century, Impolitic Bodies. Delany repeats the claim that Sorel bared her breasts (not one cheeky boob!) but this seems to stem from Georges Chastellain’s remark that Sorel was the producer and inventor of ribald fashions, and Jean Jouvenal des Ursins opining that the king ought to put a stop to feminine sartorial faults at court, including openings in the dress through which the breasts and nipples could be seen. It seems likely the ladies of the French court were pushing their boob game to new heights, but neither of these quotations suggest a nonchalant breast being popped out of one side of a tight bodice. Instead, the real scandal is that here we have a fashionable young woman openly in a sexual relationship with the king being depicted as the holiest, most beautiful and least sexual of women imaginable: the ever-Virgin Mary.

This image raises all sorts of fascinating questions about Sorel’s status at court, about art as a political statement, and about the sexual culture of the fifteenth-century French court. It doesn’t actually tell us a whole bunch about breasts or medieval fashion, and nor does the sixteenth-century fanart Wright put alongside Fouquet’s to suggest to her twitter audience that there are multiple contemporary images (or indeed, any historical sources) that show Sorel introducing a sexy, daring fashion trend.

This is a lot of virtual ink to have spilled about one particular twitter thread. But it got me thinking about Sexy History on Twitter Dot Com, which has become a whole subgenre. You know the type: someone sticks up a picture of an Inspirational Badass Woman of the Past, tweets up a storm about them, it gets thousands of retweets and people go away having learned some new history. Which it seems curmudgeonly to critique, the kind of thing done by academics who are invested in maintaining ivory towers. Well, I hope you all know that I like breaking down barriers within and outside the academy, and am not by any means a prude! What this and similar threads made me think about more broadly was what obligations to my historical subjects I have as a historian, and the answer I keep coming back to is respecting their innate human dignity.

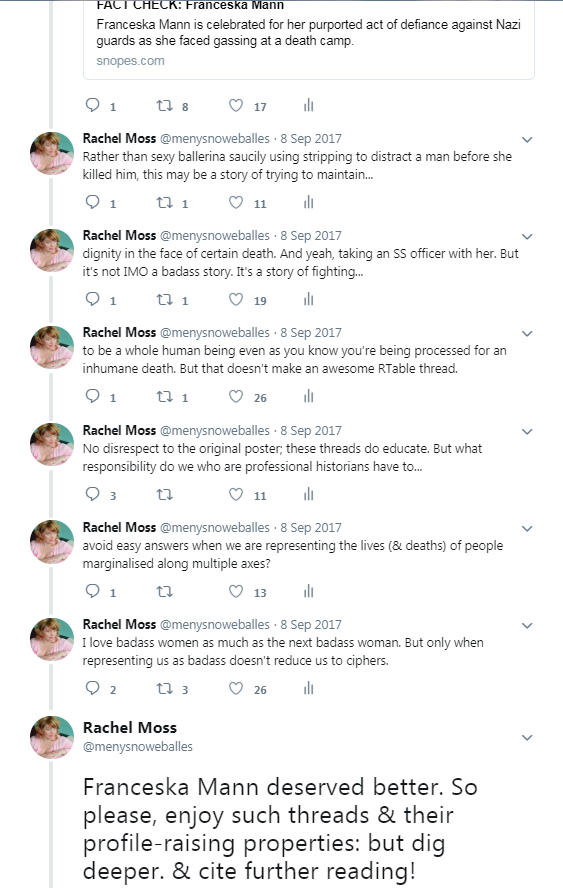

Back in 2017, I critiqued a popular thread about the ballerina and Auschwitz victim Franceska Mann. Accompanied by a glamorous photograph of the young Mann, we were regaled with a story of how Mann supposedly stripped to distract an SS officer before shooting him. What a badass! Except that the story was probably not true in those particulars, and what was true spoke more of a brave and desperate insistence on maintaining her dignity at the last rather than a bold and sexy bid for freedom.

As I said back in 2017, “I love badass women as much as the next badass woman. But only when representing us as badass doesn’t reduce us to ciphers.” The problem with a lot of these Sexy History threads is that they flatten lived human experience of the past into entertaining anecdotes. They also tend to ascribe modern motivations and desires to people (usually women) of the past, turning historical subjects into modern women in costume.

As a professional historian (for whatever that’s worth), I believe that there is an important ethical dimension to how I portray people who lived in the past. While my own work tends to take a postmodernist approach of treating texts as fictions, that doesn’t mean I believe I have the right to fictionalise others’ lived experiences to fit my narrative agenda. Of course I am sure I’ve been guilty of this – it’s not possible to write objectively. But instead of churning out twitter threads about pistol-wielding ballerinas that diminishes the dehumanizing horror of the Holocaust, or writing popular books with titles that reduce their subjects to objects (Tim Desmondes’ Agnes Sorel: The Breast And Crotch That Changed History is a horrendous 2009 example), we might perhaps think of ways to use these eye-catching incidents in history to engage with the public in ways that reveal, rather than diminish, our historical subjects. One easy way to do this: after fact-checking your Sexy History thread, also think: am I reducing this fascinating, whole human being to one incident or facet of their lived experience? Can I add a bit of historical context to my thread without derailing my narrative – and if it derails my narrative to do so, does that mean I’m not actually writing very good history? Should I add some tweets at the end of my thread with further reading for my interested audience? (The answer to the last question is always yes.) Now you can write twitter threads as long as your arm and with 280 characters per tweet, there’s really no excuse for leaving out the barest smidgen of historical context, or thanking the scholars whose work you are drawing on. Most importantly, you do more honour to the Badass Ladies of History you’re celebrating by placing them more firmly in a place we can attempt to understand their values, imagination and strength, rather than ascribing our own values wholesale to a misunderstood and murky past.

(This is why I will never have 50k+ followers on twitter, of course.)

This was absolutely fascinating. The question of her portrayal as the virgin Mary, is far more interesting as a question than wether she bared her breasts. Which seeks to further depict women as the whore, displaying their bodies for the male gaze to be judged centuries later.

I’d gladly add to be one of those twitter followers. The road to 40k

ha, thank you!

I won’t post a comment on the blog this time, as nobody wants to read what I say. But once again, you make me laugh and think. Both can be painful, but not with your blogs.

Keep prodding!

Best wishes

Richard

________________________________ From: Rachel E. Moss Sent: Friday, May 11, 2018 12:14 PM To: richardpmsykes@hotmail.com Subject: [New post] Unsexy History: Writing with Respect

menysnoweballes posted: ” Over the past few days, 53,000 peop

I’m always happy to hear from you!

I’ve just found your blog and I’m absolutely in love with it – as a history student about to take an exam in theories of history (specifically focused on gender history and postmodernism) this article and others has been so helpful for me, your approach really highlights the nuance of history writing which I want to be able to express myself!

That’s great to read. Good luck in your exams!

except denial of existence of human sexuality in history i dont understand what this article is trying to tell . neither i think its autor knows.

I have one or two ideas… 🙂